This is a readalong review. It will make more sense if you have a copy of the mag at hand.

If “Southwest Art” and “Art of the West” are for the buyer and gallery owner, “International Artist.Com” is pitched at the artist his or her self. But since the articles discuss technical matters, they are an excellent way to learn more as a consumer as well. The other contrast is that this is an explicitly planet-wide mag, while SW Art is defining itself as “today’s West” and “Art of the West” speaks for itself. But since “International Artist” mostly deals with realistic landscape, still life and figures, most of it is relevant.

A quick exception might be (oh, not necessarily) Bruno Surdo’s “Re-Emergence of Venus” which is a fabulous near-fresco of the familiar “Venus on the Half-Shell” or more formally Botticelli’s “Emergence of Venus” -- she is supposed to rise from the sea, you know, except here it’s the sewer. All the mythological characters are translated into familiar wacky denizens of Chicago. A person could look at this for hours and still see new things. The org behind this mag gave it a $2,000 Grand Prize. Give the guy some MORE, somebody! I’m beginning to pay attention to people who have studied at the American Academy of Art in Chicago, as Surdo did, though former students say it’s not as good now.

Entrances: p. 15, Dean Mitchell’s “Down in the Quarter.” Let’s hope the place survived the New Orleans catastrophe. P.101 a near-monotone exotic stairway going up through an arch. Anna Sims of Dorset, England.

Eating establishments: p. 32 Actually this is just a photo of the Old Castle of the Smithsonian Institution, all ready for the annual Paul Beck Awards Banquet, but it is quite fabulous. p. 44 “Cafe in Amsterdam” by Richard Boyer. It’s on the river. P. 109 “My Friends” by Alexander Sergeeff is a funky place where friends do talk. In South Africa, Charles van der Merwe does pastels as follows: p. 134 A deli where a girl stubbornly reads her book outside. Also, “The Morning News” where people hurry past a table where a man lingers over his newspaper. P. 135 An elegant woman indoors alone. A woman in a long skirt drinking a cup of coffee in an empty room (actually a model taking a break.) p. 139 a woman waits at an unset table.

Nice overview article on Andrew Wyeth with old familiar pictures and some new ones. “Otherworld 2002” is an almost sci-fi view of the deluxe interior of a private plane with round portholes, through which we see Wyeth’s more familiar buildings on the ground. A very white picture.

I love the filigree level of detail in Jane Freeman’s flower portraits. They’re watercolors, very pink-and-orange, and the “Spanish Gold” onions look as glamorous as the Stargazer lilies.

p. 100 Norbert Baird of Arizona paints old abandoned machinery with beautiful results: cogs and wheels that look like flowers.

p. 106 Alexander Sergeeff paints what he calls “Inhabited Sculpture” which just means high-grade furniture in elegant surrounds.

According to Southwest Art, Harley Brown has joined CAA -- I guess I thought he already belonged. Anyway, he’s got a nice article here about how to paint, using a couple of Indians -- in Peru. He’s informal, blunt, and you’ll probably never get better advice if you’re an artist.

Except that Australian Graeme Smith’s article “5 Ways to Earn More Money” is also brisk: 1. work more hours, 2. produce more, 3. Get paid more, 4. Get others to work for you and 5. Sell your intellectual property as opposed to your time. He suggests teaching or writing. What about hooking up with a Giclee print maker? Big money but I’d be cautious.

The ads include ingenious ways to get your gear to the field or your rear on an airplane for a painting holiday. One has visions of camaraderie and a whole new approach to subject matter but unless one is the teacher, it must cost like the devil. Anyway, this follows the plein air idea of evading the studio and going outside.

Thursday, December 29, 2005

"SOUTHWEST ART" January, 2006, issue

This is a read-along. To really get the benefit you need to have a copy of the mag by your computer.

January issues of mags tend to be slender. I’ve never known whether that was the result of having to compose the issue during December or slender ad revenue in January, but it clearly has something to do with the turn of the year.

This January’s Southwest Art has a smashing cover: a red-orange tipi with big gold stars (evidently floating just above the canvas surface since they cast shadows), behind it an incandescent strip of prairie and a purple ridge and sky. The artist is R. Tom Gilleon -- see his work at www.mtntrails.net or www.borsini-burr.com. He has two characteristic subjects: big, bright, fill-the-canvas tipis and grid paintings of 9-at-one-swat Indian portraits from photos. Gilleon is a Montana (ahem) artist who has a deep background in illustration for NASA, Disney, and etc. It shows. This is no self-taught kid off a ranch, though he lives on one now. On the other hand, his experience with the West is “secondary,” that it, based on the experience of others. When an artist has a cover, the interior characteristically includes ads for the same person. pp. 5, 87, 95, and 129 (just inside the back cover).

The most remarkable article (and one of a kind I would like to see more of, though I really buy the mag to keep my “eye” trained) is the one interviewing gallery owners about what’s happening. There are surprises: for instance, I’d heard grumbling about auctions and what it does to the galleries (siphons off business, distorts pricing), but it never occurred to me that the “plein air” movement applied to exhibitions outdoors as well. Of course, in Montana the weather (wind, cold, heat) kind of discourages such events anyway, but I would have thought that damage to paintings would have been a consideration even in the SW and California. Maybe the idea is to see them in actual outdoors light, as they were painted.

One dealer thought there were “thousands” of outdoor “plein air” events! They seem to include “art walks” where streets link galleries and studios so one can tour many at one time. But the ones I know (mostly Portland, OR) were at night and rather mingled with bar hopping. Seems like an event that would attract younger buyers. Some thought plein air as a painting movement and popular genre was past its peak.

Interestingly, most said their best-selling genre was, is and always will be landscape. Easy to understand out west where there’s even such a thing as “landscape rights,” that is, value that trumps industrial invasion. Only one person thought “cowboys and Indians” were rising as subject matter. One person thought it was “light” that counts -- bright cheerful subject matter. (Gilleon has it made!)

The other big influence on galleries is pretty tricky: e commerce. The owners estimated about ten percent of their business is sales from digital photos! But when it comes to artists who are selling from their own websites the legal protocol (to say nothing of developing conventions) is still loose and sometimes troublesome. The galleries, of course, want their websites linked and preferably a referral made for sales. They like the artist to establish a “personality” and selling points at the artists’ expense. In fact, I would say the main thing these gallery owners share is the idea that the artists exist merely to feed their work into the galleries. No talk about developing careers or serving the art world. Instead, it’s calling the artist up to leave off painting and come to the gallery on a moment’s notice to greet a prospective customer. Mark Smith in San Antonio said, “We can’t accept an artist, be committed, and promote them if they can’t be 100 percent committed to us.” I thought it was the other way around!

Another example of the commodification of people, particularly those who are creative. Their work is “product.” (Same thing happening with writing.) Shocking but not surprising. In fact, I think I’ll write a novel in which an artist is destroyed by these hangers-on and wheeler-dealers, because they all have lawyers on retainer and would attack anything fact-based. Corporate-minded wolves made possible by the huge number of people who really yearn to be artists and will put up with almost anything in order to survive. Nothing new or American about it.

That rant ends here.

I liked the five big brown horses running at the viewer on page 1. They’re in the fog, manes flying, and moving fast since the title is “Coming Back.” (You could ride my old brown horse in any direction for hours and be back in twenty minutes.)

Cafe portraits: P. 4, a child by Tom Balderas -- sunshine, a striped shirt. Most likely at home. P. 32, a professional chef seen from outside. Susan Romaine. (Do these count?)

Entrances: P. 32. Two here: one a back way into a tin-top shed and the other a shadowed town alley. Both Susan Romaine -- very clean, high contrast. P. 96 Another Susan Romaine: small town store fronts cast iron alongside art deco. p. 120 store fronts “Lunch Cafe” by Red Rohall.

A favorite: p. 43, Maxine Graham Price “Golden Afternoon,” just the sort of brilliant landscape shading into abstract I love. It’s just a tiny reproduction in an ad, but I’ld like to try to copy it in paint just to absorb it more.

Who are you quoting? p. 121. Three red cats looking like Donna Howell-Sickles escapees.

Doing his own thing: p. 52 Rick Bartow has been defining his own terms for many years. He’s at the intersection of being a Viet vet and being a hunter in Oregon -- many antlers, strong dislocated men, a shaman overtone.

Terpening and clones: p.11 David Mann “Path of the Stolen Ponies;” p. 18 Terpning “Sunset for the Comanche,” p. 65 “Captured from General Crook’s Command,” “Plunder from Sonora” and “Camp at Cougar’s Den;” p. 100 a teeny version of “Camp at Cougar’s Den,” p. 128 by Jim C. Norton “Washing on Salt Creek” This won the Ray Swanson Memorial Award for “communicating a moment in time and capturing the emotion of that moment.” Huh? I thought that’s what all art did. This is a nice piece of narration -- Indians on horseback entering a stream where a woman and child have been doing the wash.

Most startling: p. 83, a human heart carved in wood and inlaid with silver (or so it appears) but with a blackened top. Wickedness? A heart attack? Beautiful and intriguing. A good runner-up is a humorous religious sculpture by Maryella Fetzer, “Jonah Spit from the Belly of the Whale.” He’s movin’ fast and has big feet. He’s gonna be awful sore in the morning. P. 115?

Nice portrait: p. 119 “Sky of Hearts” by Paul Cunningham.

Grid painting: Aside from Gilleon, abstract landscapes by James Lavadour: “Deep Moon.” P. 126 Cactus by Chris Hamman, I guess. Shortage of info.

Missing in action: What?? No Pino?

NO PHONY SE ASIA KNOCKOFFS OF BRONZES IN THE ADS!! YAY! HOORAY!

AUCTION HIGHS: Cowboy Artists of America (who seem to go by CA now, instead of CAA -- is this a drop in patriotism??) $2.3 million total. No mention of top individual prices.

Altermann $3.6 million. Joseph Henry Sharp’s “Chant to the Rain Gods” went for $219,500. The painting doesn’t even look like a Sharp to me, but I prefer his landscapes. G. Harvey’s “Twilight in the City” went for $214,000 and Clark Hulings’ “Flower Market at Aix en Provence” went for $192,000. Note there are no cowboys or Indians in these two high-dollar paintings.

January issues of mags tend to be slender. I’ve never known whether that was the result of having to compose the issue during December or slender ad revenue in January, but it clearly has something to do with the turn of the year.

This January’s Southwest Art has a smashing cover: a red-orange tipi with big gold stars (evidently floating just above the canvas surface since they cast shadows), behind it an incandescent strip of prairie and a purple ridge and sky. The artist is R. Tom Gilleon -- see his work at www.mtntrails.net or www.borsini-burr.com. He has two characteristic subjects: big, bright, fill-the-canvas tipis and grid paintings of 9-at-one-swat Indian portraits from photos. Gilleon is a Montana (ahem) artist who has a deep background in illustration for NASA, Disney, and etc. It shows. This is no self-taught kid off a ranch, though he lives on one now. On the other hand, his experience with the West is “secondary,” that it, based on the experience of others. When an artist has a cover, the interior characteristically includes ads for the same person. pp. 5, 87, 95, and 129 (just inside the back cover).

The most remarkable article (and one of a kind I would like to see more of, though I really buy the mag to keep my “eye” trained) is the one interviewing gallery owners about what’s happening. There are surprises: for instance, I’d heard grumbling about auctions and what it does to the galleries (siphons off business, distorts pricing), but it never occurred to me that the “plein air” movement applied to exhibitions outdoors as well. Of course, in Montana the weather (wind, cold, heat) kind of discourages such events anyway, but I would have thought that damage to paintings would have been a consideration even in the SW and California. Maybe the idea is to see them in actual outdoors light, as they were painted.

One dealer thought there were “thousands” of outdoor “plein air” events! They seem to include “art walks” where streets link galleries and studios so one can tour many at one time. But the ones I know (mostly Portland, OR) were at night and rather mingled with bar hopping. Seems like an event that would attract younger buyers. Some thought plein air as a painting movement and popular genre was past its peak.

Interestingly, most said their best-selling genre was, is and always will be landscape. Easy to understand out west where there’s even such a thing as “landscape rights,” that is, value that trumps industrial invasion. Only one person thought “cowboys and Indians” were rising as subject matter. One person thought it was “light” that counts -- bright cheerful subject matter. (Gilleon has it made!)

The other big influence on galleries is pretty tricky: e commerce. The owners estimated about ten percent of their business is sales from digital photos! But when it comes to artists who are selling from their own websites the legal protocol (to say nothing of developing conventions) is still loose and sometimes troublesome. The galleries, of course, want their websites linked and preferably a referral made for sales. They like the artist to establish a “personality” and selling points at the artists’ expense. In fact, I would say the main thing these gallery owners share is the idea that the artists exist merely to feed their work into the galleries. No talk about developing careers or serving the art world. Instead, it’s calling the artist up to leave off painting and come to the gallery on a moment’s notice to greet a prospective customer. Mark Smith in San Antonio said, “We can’t accept an artist, be committed, and promote them if they can’t be 100 percent committed to us.” I thought it was the other way around!

Another example of the commodification of people, particularly those who are creative. Their work is “product.” (Same thing happening with writing.) Shocking but not surprising. In fact, I think I’ll write a novel in which an artist is destroyed by these hangers-on and wheeler-dealers, because they all have lawyers on retainer and would attack anything fact-based. Corporate-minded wolves made possible by the huge number of people who really yearn to be artists and will put up with almost anything in order to survive. Nothing new or American about it.

That rant ends here.

I liked the five big brown horses running at the viewer on page 1. They’re in the fog, manes flying, and moving fast since the title is “Coming Back.” (You could ride my old brown horse in any direction for hours and be back in twenty minutes.)

Cafe portraits: P. 4, a child by Tom Balderas -- sunshine, a striped shirt. Most likely at home. P. 32, a professional chef seen from outside. Susan Romaine. (Do these count?)

Entrances: P. 32. Two here: one a back way into a tin-top shed and the other a shadowed town alley. Both Susan Romaine -- very clean, high contrast. P. 96 Another Susan Romaine: small town store fronts cast iron alongside art deco. p. 120 store fronts “Lunch Cafe” by Red Rohall.

A favorite: p. 43, Maxine Graham Price “Golden Afternoon,” just the sort of brilliant landscape shading into abstract I love. It’s just a tiny reproduction in an ad, but I’ld like to try to copy it in paint just to absorb it more.

Who are you quoting? p. 121. Three red cats looking like Donna Howell-Sickles escapees.

Doing his own thing: p. 52 Rick Bartow has been defining his own terms for many years. He’s at the intersection of being a Viet vet and being a hunter in Oregon -- many antlers, strong dislocated men, a shaman overtone.

Terpening and clones: p.11 David Mann “Path of the Stolen Ponies;” p. 18 Terpning “Sunset for the Comanche,” p. 65 “Captured from General Crook’s Command,” “Plunder from Sonora” and “Camp at Cougar’s Den;” p. 100 a teeny version of “Camp at Cougar’s Den,” p. 128 by Jim C. Norton “Washing on Salt Creek” This won the Ray Swanson Memorial Award for “communicating a moment in time and capturing the emotion of that moment.” Huh? I thought that’s what all art did. This is a nice piece of narration -- Indians on horseback entering a stream where a woman and child have been doing the wash.

Most startling: p. 83, a human heart carved in wood and inlaid with silver (or so it appears) but with a blackened top. Wickedness? A heart attack? Beautiful and intriguing. A good runner-up is a humorous religious sculpture by Maryella Fetzer, “Jonah Spit from the Belly of the Whale.” He’s movin’ fast and has big feet. He’s gonna be awful sore in the morning. P. 115?

Nice portrait: p. 119 “Sky of Hearts” by Paul Cunningham.

Grid painting: Aside from Gilleon, abstract landscapes by James Lavadour: “Deep Moon.” P. 126 Cactus by Chris Hamman, I guess. Shortage of info.

Missing in action: What?? No Pino?

NO PHONY SE ASIA KNOCKOFFS OF BRONZES IN THE ADS!! YAY! HOORAY!

AUCTION HIGHS: Cowboy Artists of America (who seem to go by CA now, instead of CAA -- is this a drop in patriotism??) $2.3 million total. No mention of top individual prices.

Altermann $3.6 million. Joseph Henry Sharp’s “Chant to the Rain Gods” went for $219,500. The painting doesn’t even look like a Sharp to me, but I prefer his landscapes. G. Harvey’s “Twilight in the City” went for $214,000 and Clark Hulings’ “Flower Market at Aix en Provence” went for $192,000. Note there are no cowboys or Indians in these two high-dollar paintings.

Wednesday, December 07, 2005

Dale Burk and Northern Plains Art

Dale Burk and his brother Stoney (who is my lawyer) are examples of the intelligent, educated, resilient outdoorsmen who were reared on the East Slope of the Rockies. Stoney was a jet fighter pilot for 17 years, is a staunch defender of the Right to Bear Arms, and does a lot of pro bono work for environmental groups. In the beginning he helped Dale get started, which accounts for the name of Dale's press: Stoneydale. Stoney is on the edge of retirement and wants to learn to paint.

Dale's press (actually, I should say that it is emphatically his wife Patricia's press as well) is focused on hunting and fishing, with a bit of history and maybe some cooking. Before he had a press he was a writer and reporter, receiving a Nieman Fellowship for Professional Journalists for 1975-76 at Harvard.

In 1969 Dale published "New Interpretations," a book of essays about 22 Montana artists, which I will list because people are now looking for information about many of these people. (If this describes yourself, you might check AskArt.com, which maintains a humonguous database.) An asterisk marks those who are deceased:

*Ace Powell (1912- 1978)

*Leroy Greene (1893 - 1978)

*Albert Racine

*Branson Stevenson

Elmer Sprunger (1919 - )

*Irvin “Shorty” Shope (1900 - 1975)

*Bob Scriver (1914 - 1999)

Fred Fellows (1934 - )

*Elizabeth Lochrie (1890 - 1981)

*J. K. Ralston (1896 - 1987)

*Hugh Hockaday (1892 - 1968)

Les Welliver (1920 - )

Bob Morgan (1929 - )

Gary Schildt (1938 - )

*Merle Olson (1910 - )

Bob Emerson

Stan Lynde (1931 -

Les Peters (1916 - )

*John Clarke (1881 - 1970)

Jim Haughey

*Leo Beaulaurier (1911 - 1984)

Rex Rieke

Some of these may also be deceased, but I just don't know it. When I joined Bob Scriver in 1961, these were the Montana artists who were at their peak and selling well. They ranged in style and socioeconomics all over the place. Al Racine was a Blackfeet contemporary with Bob, Branson Stevenson and Leroy Greene were patricians, John Clarke was also a Blackfeet but one who already belonged to history, Elizabeth Lochrie was a student of Winold Reiss, Hugh Hockaday now has a museum named for him, Bob Morgan has become a kind of guiding saint in Helena, as Ace Powell was in those days in Hungry Horse, Fred Fellows is still working but has gone back to the warm weather in the southwest, and Stan Lynde is as handsome and gracious as ever, still turning out fine work -- and so on.

If I had to name the major Western artists -- or even just the Montana artists today, I wouldn't know where to go for a definitive list. There are hordes of artists, many doing exceptional work, almost too many to cram into the motel that hosts the annual C.M. Russell Western Art Auction in March. (You might start checking their website -- the jurors have done their work for this year: chosen the paintings and assigned the prizes.) In fact, this auction has had a lot to do with inspiring so many artists, and so did Burk's book profiling these early standout people.

Dale Burk's second book is more analytical. "A Brush with the West" begins with a discussion of how the Northern Rockies has a mystical presence and romantic history. Then he reviews some of the early artists -- not just Charley Russell, who dominates all conversations, but also Catlin, Bodmer, Rungius, Schreyvogel and so on. He tells how people developed realistic art in a time when the Easterners were still 'wrastling with stuff that didn't look like anything. Then the galvanic shock of losing the Russell Mint Collection to an out-of-state buyer suddenly woke Montana to the fact that the larger world had been thinking about Western art after all. The rest of the book discusses the shaping forces that have brought us to the present art scene.

Watch Stoneydale Press for reissues of these books. Otherwise, one must keep checking such online used book sources as Powells.com, Abebooks.com, and Alibris.com.

"New Interpretations" by Dale A. Burk, 1969. Library of Congress Cat.Card No. 82-99859

"A Brush with the West" by Dale A. Burk, 1980. ISBN 0-87842-133-5

(I apologize for writing my name on the front of "New Interpretations." I was afraid it would sprout legs and walk off. These are working books and I pack them around with me.)

www.stoneydalepress.com

Stevensville, MT 59870

Dale's press (actually, I should say that it is emphatically his wife Patricia's press as well) is focused on hunting and fishing, with a bit of history and maybe some cooking. Before he had a press he was a writer and reporter, receiving a Nieman Fellowship for Professional Journalists for 1975-76 at Harvard.

In 1969 Dale published "New Interpretations," a book of essays about 22 Montana artists, which I will list because people are now looking for information about many of these people. (If this describes yourself, you might check AskArt.com, which maintains a humonguous database.) An asterisk marks those who are deceased:

*Ace Powell (1912- 1978)

*Leroy Greene (1893 - 1978)

*Albert Racine

*Branson Stevenson

Elmer Sprunger (1919 - )

*Irvin “Shorty” Shope (1900 - 1975)

*Bob Scriver (1914 - 1999)

Fred Fellows (1934 - )

*Elizabeth Lochrie (1890 - 1981)

*J. K. Ralston (1896 - 1987)

*Hugh Hockaday (1892 - 1968)

Les Welliver (1920 - )

Bob Morgan (1929 - )

Gary Schildt (1938 - )

*Merle Olson (1910 - )

Bob Emerson

Stan Lynde (1931 -

Les Peters (1916 - )

*John Clarke (1881 - 1970)

Jim Haughey

*Leo Beaulaurier (1911 - 1984)

Rex Rieke

Some of these may also be deceased, but I just don't know it. When I joined Bob Scriver in 1961, these were the Montana artists who were at their peak and selling well. They ranged in style and socioeconomics all over the place. Al Racine was a Blackfeet contemporary with Bob, Branson Stevenson and Leroy Greene were patricians, John Clarke was also a Blackfeet but one who already belonged to history, Elizabeth Lochrie was a student of Winold Reiss, Hugh Hockaday now has a museum named for him, Bob Morgan has become a kind of guiding saint in Helena, as Ace Powell was in those days in Hungry Horse, Fred Fellows is still working but has gone back to the warm weather in the southwest, and Stan Lynde is as handsome and gracious as ever, still turning out fine work -- and so on.

If I had to name the major Western artists -- or even just the Montana artists today, I wouldn't know where to go for a definitive list. There are hordes of artists, many doing exceptional work, almost too many to cram into the motel that hosts the annual C.M. Russell Western Art Auction in March. (You might start checking their website -- the jurors have done their work for this year: chosen the paintings and assigned the prizes.) In fact, this auction has had a lot to do with inspiring so many artists, and so did Burk's book profiling these early standout people.

Dale Burk's second book is more analytical. "A Brush with the West" begins with a discussion of how the Northern Rockies has a mystical presence and romantic history. Then he reviews some of the early artists -- not just Charley Russell, who dominates all conversations, but also Catlin, Bodmer, Rungius, Schreyvogel and so on. He tells how people developed realistic art in a time when the Easterners were still 'wrastling with stuff that didn't look like anything. Then the galvanic shock of losing the Russell Mint Collection to an out-of-state buyer suddenly woke Montana to the fact that the larger world had been thinking about Western art after all. The rest of the book discusses the shaping forces that have brought us to the present art scene.

Watch Stoneydale Press for reissues of these books. Otherwise, one must keep checking such online used book sources as Powells.com, Abebooks.com, and Alibris.com.

"New Interpretations" by Dale A. Burk, 1969. Library of Congress Cat.Card No. 82-99859

"A Brush with the West" by Dale A. Burk, 1980. ISBN 0-87842-133-5

(I apologize for writing my name on the front of "New Interpretations." I was afraid it would sprout legs and walk off. These are working books and I pack them around with me.)

www.stoneydalepress.com

Stevensville, MT 59870

Tuesday, December 06, 2005

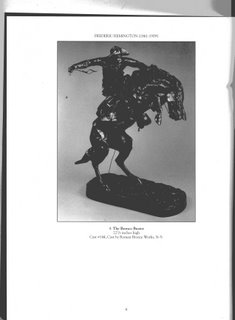

"The Bronco Buster"

This Remington bronze is so emblematic of Western bronzes in general that it is worth pondering for a moment. This photo is from a 1996 Mongerson/Wunderlich Gallery catalogue. The gallery was in Chicago and was linked to a different Mongerson and Wunderlich partnership, which was the marriage of the two parties. Previously, Rudi Wunderlich had been a co-owner of the Kennedy Galleries in New York City, one of the most important galleries handling Western art. For instance, they were Harry Jackson's gallery. As far as I can tell, the Mongerson/Wunderlich Gallery is currently in limbo.

This is what Rudi says about this bronze: "Many of the period sculptures had their bronzes cast at Bertelli's Roman Bronze Works. Remington's first bronze and signature piece, Bronco Buster, was cast first with the sand casting method by Henry-Bonnard Foundry. We know of 64 casts produced by this method. Then Remington went with Bertelli to Roman Bronze Works of which approximately 90 casts were produced before Remington's death."

This photo is of cast #144. If the same mold was used straight through, it would have lost a certain amount of detail. (More if the mold were made of traditional materials, less if the mold were made with modern materials, which it likely was not.) Remington is known to have enjoyed going to the foundry to work on the wax, sometimes making rather drastic changes -- moving arms, converting leather chaps to fur chaps and so on. In a sense, he was creating "one of a kind" bronzes. Otherwise, for modern sculptors there were an unusually large number of castings.

What confuses the issue is that this piece is so popular (one often sees a casting behind the President of the USA in the Oval Office) that many knock-offs have been made. The best would have been castings made from molds made from an original. The worst would be the ones made by SE Asia craftsmen working from photos. The cheapest ones are only a few hundred dollars, though their owners often believe they have "real" Remington castings.

But here's a problem no one anticipated: breaking a horse this way is now considered "cruel" by many people who have seen or read "The Horse Whisperer," so suddenly this bronze is "politically incorrect." Now what? Where is a bronze of a "horse whisperer?" Who would buy it?

Sunday, November 27, 2005

Art of the West, notes on Nov/Dec 2005

Yellow slickers: P. 21 Kelly Donovan’s “Easy Goin” -- horses crossing a river.p. 65. Packer on a white horse by Gary Lynn Roberts. All his primary riders look the same.

Eating places: Couldn’t see any. Maybe you can.

Doorways: p. 40 Schmid’s “Red Door II,” only 8”x7” but quite sophisticated composition of a European stone building with a fellow in a beret standiing outside reading the newspaper.

p. 58: Front door of the San Jose Church by Walt Gonske. Strong simple adobe lines against a dark blue sky.

Pino ad on page 19. I don’t know how to “do” links, but if you go to this URL: http://www.2blowhards.com/archives/002311.html There’s an interesting discussion about Pino. He’s another of the paperback cover artists and illustrators (like Terpning and many others) who has moved over to easel painting.

Money reports:

Maynard Dixon Country 2005 gala made more than $250,000.

Cheyenne Frontier Days Western Art Show and Sale cleared $562,370. 179 of the 330 pieces sold.

Buff Bill Art Show and Sale totalled $905,920.

Interesting:

Roy Andersen, one of the CAA artists who withdrew, has a triptych featured on p. 84. 52” tall and a total of 152” wide, in three pieces, narrating an invented Crow story against a lurid red sky. I’ll pass. (In generaI I find most paintings of Indians pretty bogus or amateur.)

I liked the Peter Brooke bronze portrait of “Michael, Standing” on p. 85. Another I liked was on page 87: Krystii Melaine’s “After Rain,” a man leading a dapple-gray team across the flooded creek. Very simple and real. On p. 93 is a strong bronze bust of a Huron with the patina very well handled. It’s by Barbara Kiwak.

But the real reason for some to buy and hoard this issue is the well-illustrated story of John Clymer’s Lewis & Clark series. (A dozen paintings.) John was another professional illustrator, well-known for his Sat. Eve. Post covers and for reconstructions of other times and places for National Geographic. He was a narrative artist who was careful to do research with the help of Doris, his wife. They often stopped to visit Bob Scriver in Browning, swapping art lessons for anatomy lessons, and even gave us a wedding gift, a very large illustration of a James Willard Schultz story about bison running through camp, tearing up and knocking down everything. (Later I used to claim it was an illustration of our own marriage.)

Clymer’s colors tended towards the pastel, almost a watercolor palette, which is appropriate for the open prairie and seaside vignettes. They are carefully composed, usually along diagonals and curves that guide the eye to the people, which have a similar “Clymer” look though they are costumed authentically and have distinguishable faces, at least in the case of those who left portraits or -- like York -- suggest something specific. It is the people that count, though the scenery is beautiful, and it would be interesting to compare painting-by-painting with Charles Fritz’ series. I don’t have a copy of Fritz’ book, but my memory is that he is following geography more than anecdote.

John was one of the CAA members who didn’t go on horseback but he was a Westerner -- just not from the prairie. He was also well-connected and respected around Connecticut and one of the early members of the Society of Animal Artists and other professional groups. He was a mild and honorable man who never did harm, held a grudge, or worked an angle as nearly as I could tell. If he had, I think Doris would have straightened him out.

When I was a little child, I tore Clymer’s painting of stampeding horses out of a magazine. It was a double-page ad for a gasoline company, as I recall, and I had no idea who John was at that time. Bob said he took a terrible ribbing about the picture because there was absolutely no dust raised by those trampling hooves! I didn’t care about realism. To me they were like Varga girls, beautiful pastel living flesh.

Eating places: Couldn’t see any. Maybe you can.

Doorways: p. 40 Schmid’s “Red Door II,” only 8”x7” but quite sophisticated composition of a European stone building with a fellow in a beret standiing outside reading the newspaper.

p. 58: Front door of the San Jose Church by Walt Gonske. Strong simple adobe lines against a dark blue sky.

Pino ad on page 19. I don’t know how to “do” links, but if you go to this URL: http://www.2blowhards.com/archives/002311.html There’s an interesting discussion about Pino. He’s another of the paperback cover artists and illustrators (like Terpning and many others) who has moved over to easel painting.

Money reports:

Maynard Dixon Country 2005 gala made more than $250,000.

Cheyenne Frontier Days Western Art Show and Sale cleared $562,370. 179 of the 330 pieces sold.

Buff Bill Art Show and Sale totalled $905,920.

Interesting:

Roy Andersen, one of the CAA artists who withdrew, has a triptych featured on p. 84. 52” tall and a total of 152” wide, in three pieces, narrating an invented Crow story against a lurid red sky. I’ll pass. (In generaI I find most paintings of Indians pretty bogus or amateur.)

I liked the Peter Brooke bronze portrait of “Michael, Standing” on p. 85. Another I liked was on page 87: Krystii Melaine’s “After Rain,” a man leading a dapple-gray team across the flooded creek. Very simple and real. On p. 93 is a strong bronze bust of a Huron with the patina very well handled. It’s by Barbara Kiwak.

But the real reason for some to buy and hoard this issue is the well-illustrated story of John Clymer’s Lewis & Clark series. (A dozen paintings.) John was another professional illustrator, well-known for his Sat. Eve. Post covers and for reconstructions of other times and places for National Geographic. He was a narrative artist who was careful to do research with the help of Doris, his wife. They often stopped to visit Bob Scriver in Browning, swapping art lessons for anatomy lessons, and even gave us a wedding gift, a very large illustration of a James Willard Schultz story about bison running through camp, tearing up and knocking down everything. (Later I used to claim it was an illustration of our own marriage.)

Clymer’s colors tended towards the pastel, almost a watercolor palette, which is appropriate for the open prairie and seaside vignettes. They are carefully composed, usually along diagonals and curves that guide the eye to the people, which have a similar “Clymer” look though they are costumed authentically and have distinguishable faces, at least in the case of those who left portraits or -- like York -- suggest something specific. It is the people that count, though the scenery is beautiful, and it would be interesting to compare painting-by-painting with Charles Fritz’ series. I don’t have a copy of Fritz’ book, but my memory is that he is following geography more than anecdote.

John was one of the CAA members who didn’t go on horseback but he was a Westerner -- just not from the prairie. He was also well-connected and respected around Connecticut and one of the early members of the Society of Animal Artists and other professional groups. He was a mild and honorable man who never did harm, held a grudge, or worked an angle as nearly as I could tell. If he had, I think Doris would have straightened him out.

When I was a little child, I tore Clymer’s painting of stampeding horses out of a magazine. It was a double-page ad for a gasoline company, as I recall, and I had no idea who John was at that time. Bob said he took a terrible ribbing about the picture because there was absolutely no dust raised by those trampling hooves! I didn’t care about realism. To me they were like Varga girls, beautiful pastel living flesh.

The Eiteljorg Ad in SouthWest Art

In my review of the Southwest Art magazine for December, 2005, I neglected to mention that there is a "grid" painting on page 121. The subject is ochre and sienna plus darker colors (black and white in the center rectangle) and appears to be architectural in subject matter: in fact, a bridge.

The painting is by James Lavendour, a Walla Walla tribal member. It is featured in an ad by "the new" Eiteljorg Museum with the motto "Into the Fray." It announces the Eiteljorg Fellowship for Native American Fine Art 2005. I take this to mean attention to creation rather than focus on conservation of artifacts.

Raymon Gonyea, who is the curator of Indian arts at the Eiteljorg, was in Browning at the Museum of the Plains Indian in the Sixties. He was standing on sinking sands then, but he was a good friend and we learned from him.

I'll try to write more about the Eiteljorg later, though I've never been there. It's one of the newer museums of its kind.

The painting is by James Lavendour, a Walla Walla tribal member. It is featured in an ad by "the new" Eiteljorg Museum with the motto "Into the Fray." It announces the Eiteljorg Fellowship for Native American Fine Art 2005. I take this to mean attention to creation rather than focus on conservation of artifacts.

Raymon Gonyea, who is the curator of Indian arts at the Eiteljorg, was in Browning at the Museum of the Plains Indian in the Sixties. He was standing on sinking sands then, but he was a good friend and we learned from him.

I'll try to write more about the Eiteljorg later, though I've never been there. It's one of the newer museums of its kind.

Saturday, November 26, 2005

Cowboy Artists of America in December, 2005

Kristin Bucher, editor of “Southwest Art,” in her editorial for December, 2005, did a nice balancing act when talking about the most recent changes in CAA. Briefly, she told us that some important members have been lost: Ray Swanson (deceased young), Roy Anderson, Robert Pummill and Jim Reynolds (the original “yellow slicker” artist -- his are often wet with rain).

On the other hand, the group -- which no one on the outside expected to persist, since keeping “cowboy artists” within a boundary is roughly like herding cats -- has met its fortieth anniversary. They did a smart thing: returned to the former Oak Creek Tavern in Sedona, AZ, where the organization originated in the high spirits resulting from participating in a trail drive. I wonder who actually attended.

Kristin notes that the group includes a couple of dozen members, but I think the original membership was quite a bit smaller and the number of members who have traveled through is MUCH larger. For a while there were female members. For a while there were “associates,” sort of aspiring CAA members. I’d like to see a list of ALL the members of every sort. The four who left this time had been long-time members.

An organization cannot last forty years without changing with the times, but CAA leapt from a scene where “cowboy artists” were just a kind of folk phenomenon, to a market today that approaches a million dollars per painting. (For some reason, though sculpture is more expensive to produce, it’s the paintings that get the high prices.) The original premise of CAA was that all the artists were especially good because they were actual practicing cowboys who could at least ride and were REQUIRED to show up once in a while to ride and re-”bond” with the other members. In those days, it was assumed that authenticity was one of the major dimensions of good cowboy art. One of the continuing tensions in the group was that some were better at drawing or whatever than others were, but they were good buddies, had been there at the beginning, and WERE cowboys.

Now people want to join because the quality of the art as art is high so that art buyers who can’t really tell what’s good will have some assurance. The reason the art has become so good is because of the migration of trained illustrators out of the NE into SW studios. Today’s CAA members might or might not have a little cowboy in their background. (Of course, that migration happened a few decades ago and many of those folks have aged and gone on ahead.) What’s more painful is that the camaraderie -- one for all and all for one -- seems to be breaking down as skill and high sale prices become the more important criteria. The gentlemen’s code of the NE artists has also been left behind.

The departure of the noted artists is probably not as serious as the hardening of attitudes and business practices (which have always been contentious) brought on by association with the print industry. The people who put out prints are frankly corporate and their lawyers are steely. Artists who are bound to them by contracts and big incomes soon realize they are captives.

This has lead to a souring of relationships with secondary businesses like index websites, for instance, “AskArt.com” which also had a major gunslinger-type shootout last summer with CAA. I have no idea whether this is related to the leaving of the four artists. AskArt deleted all CAA members in the aftermath of CAA lawyers’ accusations over photos of the art, which seemed to be only the mask for the real issue: AskArt publishes auction results and some artists were not doing well at auction. (At least one artist who stepped out of CAA is now posted on AskArt again. The website is a major source of information for curators, buyers, writers, and so on.)

So Western art auctions, which have contributed to the major jumps in price, have also made some artists vulnerable. There are a lot of them, the prices are taken as indicators of quality whether or not they actually are, and the artists cannot control them. They tell me that when Bob Scriver’s bronzes didn’t sell well at auction, his fourth wife actually wept. (Of course, she drank and that makes people sentimental.)

Cowboy Artists of America are used to being admired. Those who weren’t, quietly stepped out. And one of the by-products of this admiration is that people collect artists as much as their art. So buyers expect to be guests in the artist’s home, expect “their” artists to attend their social events, and so on. This is a corporate model, maybe, except no golf. But it is very high pressure, esp. for people who are naturally more attuned to long days at the easel in their studio. There is often great emphasis on how congenial a particular artist might be. In my experience, these individuals are likely to be people who praise your spouse on top of the table and kick your dog under the table.

One of these people swept in here to the Blackfeet reservation a few years ago with a lot of giclee prints under his arm (instead of beads and silk ribbons), demanded a lot of accommodation in terms of rounding up scenes and models he could photograph, and left at the end of a week or so. He and his print company has made millions, the local people have giclee prints on their walls without really knowing what they are, and this artist has moved on to the next reservation -- all while claiming enormous rapport and sympathy with Blackfeet, about which he knows little or nothing. This observer was not impressed.

I wonder whether CAA could persist if Joe Beeler, one of the founders, were to be lost from the group. His personality seems to exceed all the others even as he tries to be inclusive. He is a carrier of the original CAA vision and often a diplomat in their midst.

On the other hand, the group -- which no one on the outside expected to persist, since keeping “cowboy artists” within a boundary is roughly like herding cats -- has met its fortieth anniversary. They did a smart thing: returned to the former Oak Creek Tavern in Sedona, AZ, where the organization originated in the high spirits resulting from participating in a trail drive. I wonder who actually attended.

Kristin notes that the group includes a couple of dozen members, but I think the original membership was quite a bit smaller and the number of members who have traveled through is MUCH larger. For a while there were female members. For a while there were “associates,” sort of aspiring CAA members. I’d like to see a list of ALL the members of every sort. The four who left this time had been long-time members.

An organization cannot last forty years without changing with the times, but CAA leapt from a scene where “cowboy artists” were just a kind of folk phenomenon, to a market today that approaches a million dollars per painting. (For some reason, though sculpture is more expensive to produce, it’s the paintings that get the high prices.) The original premise of CAA was that all the artists were especially good because they were actual practicing cowboys who could at least ride and were REQUIRED to show up once in a while to ride and re-”bond” with the other members. In those days, it was assumed that authenticity was one of the major dimensions of good cowboy art. One of the continuing tensions in the group was that some were better at drawing or whatever than others were, but they were good buddies, had been there at the beginning, and WERE cowboys.

Now people want to join because the quality of the art as art is high so that art buyers who can’t really tell what’s good will have some assurance. The reason the art has become so good is because of the migration of trained illustrators out of the NE into SW studios. Today’s CAA members might or might not have a little cowboy in their background. (Of course, that migration happened a few decades ago and many of those folks have aged and gone on ahead.) What’s more painful is that the camaraderie -- one for all and all for one -- seems to be breaking down as skill and high sale prices become the more important criteria. The gentlemen’s code of the NE artists has also been left behind.

The departure of the noted artists is probably not as serious as the hardening of attitudes and business practices (which have always been contentious) brought on by association with the print industry. The people who put out prints are frankly corporate and their lawyers are steely. Artists who are bound to them by contracts and big incomes soon realize they are captives.

This has lead to a souring of relationships with secondary businesses like index websites, for instance, “AskArt.com” which also had a major gunslinger-type shootout last summer with CAA. I have no idea whether this is related to the leaving of the four artists. AskArt deleted all CAA members in the aftermath of CAA lawyers’ accusations over photos of the art, which seemed to be only the mask for the real issue: AskArt publishes auction results and some artists were not doing well at auction. (At least one artist who stepped out of CAA is now posted on AskArt again. The website is a major source of information for curators, buyers, writers, and so on.)

So Western art auctions, which have contributed to the major jumps in price, have also made some artists vulnerable. There are a lot of them, the prices are taken as indicators of quality whether or not they actually are, and the artists cannot control them. They tell me that when Bob Scriver’s bronzes didn’t sell well at auction, his fourth wife actually wept. (Of course, she drank and that makes people sentimental.)

Cowboy Artists of America are used to being admired. Those who weren’t, quietly stepped out. And one of the by-products of this admiration is that people collect artists as much as their art. So buyers expect to be guests in the artist’s home, expect “their” artists to attend their social events, and so on. This is a corporate model, maybe, except no golf. But it is very high pressure, esp. for people who are naturally more attuned to long days at the easel in their studio. There is often great emphasis on how congenial a particular artist might be. In my experience, these individuals are likely to be people who praise your spouse on top of the table and kick your dog under the table.

One of these people swept in here to the Blackfeet reservation a few years ago with a lot of giclee prints under his arm (instead of beads and silk ribbons), demanded a lot of accommodation in terms of rounding up scenes and models he could photograph, and left at the end of a week or so. He and his print company has made millions, the local people have giclee prints on their walls without really knowing what they are, and this artist has moved on to the next reservation -- all while claiming enormous rapport and sympathy with Blackfeet, about which he knows little or nothing. This observer was not impressed.

I wonder whether CAA could persist if Joe Beeler, one of the founders, were to be lost from the group. His personality seems to exceed all the others even as he tries to be inclusive. He is a carrier of the original CAA vision and often a diplomat in their midst.

Friday, November 25, 2005

Southwest Art, December, 2005

“Special still-life issue”

Checklist:

Yellow slickers: p. 65. Not exactly, but a couple of James Bama guys in waxed canvas dusters.

Eating places: P. 74: Hilarie Lambert’s Parisian and tres elegante dining room. P. 78: Lindsay Goodwin’s equally elegant celebration of light, paneling and wine glasses.

Depicting writing: On pg. 58 there’s a purple rabbit typing and a lady in a patio chair with a notebook.

Doorways: p. 42 The front of a ‘dobe strung with Christmas lights. p. 67 a very fantastic and un-Western door to a house with Gothic windows and fairy in a tree out front. p. 119 Actual doors to order! Works of art, though.

Simplest: p. 107: One of the top best toys this year is a plain cardboard box. This is a painting of four plain boxes, mostly toward the top of the painting, all boxes open, welcoming.

Most complex:

Most haunting: p. 73. Oreland Joe steps away from his usual classic and restrained stone carvings to both paint and cast the same strange shape of a face topped with frondy feathers and looped with turquoise beads.

Money marks:

ARTS FOR THE PARKS, Jackson, WY:

$25,000 & gold medal to Morten Solberg for “Morning Flight,

Olympic National Park." Painting is shown on p. 128. A heron flying over a

tide.

WESTERN VISIONS MINIATURES AND MORE, also Jackson, WY:

$1,055,000 total sales.

BUFFALO BILL ART SHOW & SALE, Cody, WY:

More than $900,000 total sales. Highest yet for them.

Krystii Melaine’s “Moving Cattle” and James Bama’s “Black Elk’s

Great-Great-Grandson” each sold for $30,000.

SAN LUIS OBISPO, CA, PLEIN AIR PAINTING FESTIVAL

$111,000 total sales.

MOST OUTRAGEOUS -- even CRIMINAL:

The classified ads feature two (relatively) big color ads with the identical photo of a Remington bronze. THESE COMPANIES ARE BOGUS!! They are selling illegal replicas and castings, some of them bearing very little resemblance to the originals and some of them evidently close copies done from photos or maybe molds pulled from legitimate castings. We’ve been hearing about these bronzes, cast in SE Asia like those cheap clothes you love. They claim to be “wholesale to the public.” Believe me, there is no such thing as really fine art bronzes that are “wholesale to the public.”

Aside from their dubious source, these castings are ruining the market for authentic American Western castings because only highly experienced people can tell the knock-offs from the real thing. Some worried people simply make a rule: never buy bronzes. Amateurs are likely to end up with something that has no provenance, which is the real key to art value. (Provenance is being able to document the source of the art and the various owners until the present.) People with no real eye for art are liable to buy stuff that doesn’t even resemble what it purports to actually be. (Take a look at what is supposed to be Rodin’s “Thinker.”)

Southwest Art magazine should be embarrassed for allowing such people to run ads. It is simply false-advertising and piracy. Probably the person who runs the ad section has little contact with the editors, who presumably know better, but this is pretty serious and whoever has the authority ought to draw a line.

Checklist:

Yellow slickers: p. 65. Not exactly, but a couple of James Bama guys in waxed canvas dusters.

Eating places: P. 74: Hilarie Lambert’s Parisian and tres elegante dining room. P. 78: Lindsay Goodwin’s equally elegant celebration of light, paneling and wine glasses.

Depicting writing: On pg. 58 there’s a purple rabbit typing and a lady in a patio chair with a notebook.

Doorways: p. 42 The front of a ‘dobe strung with Christmas lights. p. 67 a very fantastic and un-Western door to a house with Gothic windows and fairy in a tree out front. p. 119 Actual doors to order! Works of art, though.

Simplest: p. 107: One of the top best toys this year is a plain cardboard box. This is a painting of four plain boxes, mostly toward the top of the painting, all boxes open, welcoming.

Most complex:

Most haunting: p. 73. Oreland Joe steps away from his usual classic and restrained stone carvings to both paint and cast the same strange shape of a face topped with frondy feathers and looped with turquoise beads.

Money marks:

ARTS FOR THE PARKS, Jackson, WY:

$25,000 & gold medal to Morten Solberg for “Morning Flight,

Olympic National Park." Painting is shown on p. 128. A heron flying over a

tide.

WESTERN VISIONS MINIATURES AND MORE, also Jackson, WY:

$1,055,000 total sales.

BUFFALO BILL ART SHOW & SALE, Cody, WY:

More than $900,000 total sales. Highest yet for them.

Krystii Melaine’s “Moving Cattle” and James Bama’s “Black Elk’s

Great-Great-Grandson” each sold for $30,000.

SAN LUIS OBISPO, CA, PLEIN AIR PAINTING FESTIVAL

$111,000 total sales.

MOST OUTRAGEOUS -- even CRIMINAL:

The classified ads feature two (relatively) big color ads with the identical photo of a Remington bronze. THESE COMPANIES ARE BOGUS!! They are selling illegal replicas and castings, some of them bearing very little resemblance to the originals and some of them evidently close copies done from photos or maybe molds pulled from legitimate castings. We’ve been hearing about these bronzes, cast in SE Asia like those cheap clothes you love. They claim to be “wholesale to the public.” Believe me, there is no such thing as really fine art bronzes that are “wholesale to the public.”

Aside from their dubious source, these castings are ruining the market for authentic American Western castings because only highly experienced people can tell the knock-offs from the real thing. Some worried people simply make a rule: never buy bronzes. Amateurs are likely to end up with something that has no provenance, which is the real key to art value. (Provenance is being able to document the source of the art and the various owners until the present.) People with no real eye for art are liable to buy stuff that doesn’t even resemble what it purports to actually be. (Take a look at what is supposed to be Rodin’s “Thinker.”)

Southwest Art magazine should be embarrassed for allowing such people to run ads. It is simply false-advertising and piracy. Probably the person who runs the ad section has little contact with the editors, who presumably know better, but this is pretty serious and whoever has the authority ought to draw a line.

Monday, November 14, 2005

Rex & Iola Breneman Bequest

Rex and Iola Breneman were customers of Bob Scriver for many years, building up a repertoire of bronzes, large and small, including some modeled specifically for them and sold with the copyright, and castings of the spectacular rodeo bronzes done at the end of the Sixties. Recently the Brenemans donated one hundred Scriver br0nzes, worth more than $350,000, to the North Dakota Cowboy Hall of Fame Center of Western Heritage and Cultures: Native Americans, Ranching and Rodeo. (The website is www.northdakotacowboy.com where you will see Teddy Roosevelt looking “bully” in hair chaps.)

Located in Medora, near Roosevelt’s ranch, the North Dakota Hall of Fame is sort of a northern counterpoint to the Oklahoma Version where another set of Scriver rodeo bronzes is located, specifically the heroic-sized portrait of Bill Linderman that got him started on rodeo subjects in the first place. The bronzes are now displayed in the traveling exhibit gallery. Dickinson State University, which Scriver attended, cooperated by storing and displaying pieces. They will circulate through the schools in the winter when the museum is closed.

Rex, a WWII and Korean War Air Corps bombardier, was a little guy -- like a cowboy -- and ran a service station in Coram on the West side of the Rockies. His wife, Iola, sometimes helped Bob corral some of his ever-expanding lists of accomplishments and new creations. Like many customers of Western artists, the Brenemans felt they were part of Bob’s family.

Iola’s nephew, Jacob Bell, also has a website featuring the collections of the Breneman’s, principally works by Scriver and his lifelong friend, Ace Powell. (http://www.bobscriver.com/) There are photos of some of the Scriver bronzes on that website as well as family snapshots and lists of sculptures with their sizes and other data. It’s unclear whether more Breneman castings of Scriver bronzes will be available in the future.

Rex himself has had a series of strokes which have narrowed his life considerably. Luckily, Iola is still her usual competent self and is coping pretty well.

Medora, North Dakota, has a wildly romantic history that is well worth researching (Medora was a real woman, the wife of a Marquis, and her elegant home remains) though it isn’t appropriate to discuss on this blog.

Located in Medora, near Roosevelt’s ranch, the North Dakota Hall of Fame is sort of a northern counterpoint to the Oklahoma Version where another set of Scriver rodeo bronzes is located, specifically the heroic-sized portrait of Bill Linderman that got him started on rodeo subjects in the first place. The bronzes are now displayed in the traveling exhibit gallery. Dickinson State University, which Scriver attended, cooperated by storing and displaying pieces. They will circulate through the schools in the winter when the museum is closed.

Rex, a WWII and Korean War Air Corps bombardier, was a little guy -- like a cowboy -- and ran a service station in Coram on the West side of the Rockies. His wife, Iola, sometimes helped Bob corral some of his ever-expanding lists of accomplishments and new creations. Like many customers of Western artists, the Brenemans felt they were part of Bob’s family.

Iola’s nephew, Jacob Bell, also has a website featuring the collections of the Breneman’s, principally works by Scriver and his lifelong friend, Ace Powell. (http://www.bobscriver.com/) There are photos of some of the Scriver bronzes on that website as well as family snapshots and lists of sculptures with their sizes and other data. It’s unclear whether more Breneman castings of Scriver bronzes will be available in the future.

Rex himself has had a series of strokes which have narrowed his life considerably. Luckily, Iola is still her usual competent self and is coping pretty well.

Medora, North Dakota, has a wildly romantic history that is well worth researching (Medora was a real woman, the wife of a Marquis, and her elegant home remains) though it isn’t appropriate to discuss on this blog.

Thursday, November 03, 2005

Arnie Olsen resigns from Montana Historical Society

http://www.helenair.com/articles/2005/11/03/montana/a01110305_03.txt

Historical Society director resigns

By CHARLES S. JOHNSON - IR State Bureau - 11/03/05

HELENA — Arnold Olsen resigned Wednesday as director of the Montana Historical Society, a job he had held since July 1999.

Olsen, 55, said he is resigning to pursue other interests related to his doctorate in wildlife biology. He said he will leave the director’s job, which pays about $97,000 a year, in a week or so.

The society’s board of trustees said it will begin an immediate search for his successor.

He previously worked for 17 to 18 years for the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks where he served as administrator of the Wildlife and Parks divisions.

Olsen resigned during the closed portion of a teleconference “special meeting” of the Historical Society’s board of trustees in the Capitol earlier in the day.

The board’s agenda announced in advance that a portion of the meeting was to be closed because “personal privacy outweighs public’s right to know,” a determination later made at the meeting. Although the agenda was posted on the Historical Society’s Web site, it was not sent to at least some news organizations prior to the meeting.

Like most society directors, Olsen had his supporters and his detractors on the board and among the agency’s various constituencies. The board oversees operations of Historical Society, which runs the state historical museum, the state archives, a history magazine, the state historical preservation office and oversees certain historical buildings.

In a telephone interview Wednesday night, Olsen said his resignation was voluntary. He said he never intended to stay as director as long as he did. Olsen said he has never remained in any one job longer than eight years.

“I have a lot of diverse interests,” Olsen said. He said he wants to remain in Helena and would like to return to the Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks for the rest of his career before retiring in four or five years.

Asked if he received a financial settlement from the board to resign, Olsen said, “All of that is private.”

The press release announcing his resignation told how Olsen spearheaded efforts for the society before the 2005 Legislature’s to secure $7.5 million in state bonding for seed money for a new Montana History Center.

The society is considering the purchase of the land and buildings where the Capital Hill Mall is now located in Helena, a few blocks north of the Capitol and converting it to a new museum and headquarters, a project estimated to cost $40 million. The society is now completing architectural and engineering studies to determine if the mall is suitable for a history center.

Olsen said the timing of his retirement was in the best interest of the completion of the project.

“Looking at the timing of my retirement, I would not be able to see this important construction project through to completion and would not want to leave at a critical juncture,” he said in the press release.

He said he got the project to the point where it needed to be with the seed money from the Legislature and the support from Gov. Brian Schweitzer.

A number of private donors are stepping up now that they’ve seen the state’s commitment to the project, Olsen said.

“The future of the society is bright, and I feel good about the contributions I have been able to make toward its success,” Olsen said. “I wish the society and the board of trustees well as they move forward with their important work.”

Among his notable other accomplishments was the acquisition of the Robert M. Scriver collection to keep it in the state of Montana, the press release said.

Olsen was the ninth professional director to head the Historical Society since 1951, when historian K. Ross Toole headed the society for seven years. Before then, the society didn’t have professional administrators. The average tenure of its professional directors has been about five years.

The Montana Historical Society was created in 1865, a year after Montana became a territory, and became a state agency in 1891.

Historical Society director resigns

By CHARLES S. JOHNSON - IR State Bureau - 11/03/05

HELENA — Arnold Olsen resigned Wednesday as director of the Montana Historical Society, a job he had held since July 1999.

Olsen, 55, said he is resigning to pursue other interests related to his doctorate in wildlife biology. He said he will leave the director’s job, which pays about $97,000 a year, in a week or so.

The society’s board of trustees said it will begin an immediate search for his successor.

He previously worked for 17 to 18 years for the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks where he served as administrator of the Wildlife and Parks divisions.

Olsen resigned during the closed portion of a teleconference “special meeting” of the Historical Society’s board of trustees in the Capitol earlier in the day.

The board’s agenda announced in advance that a portion of the meeting was to be closed because “personal privacy outweighs public’s right to know,” a determination later made at the meeting. Although the agenda was posted on the Historical Society’s Web site, it was not sent to at least some news organizations prior to the meeting.

Like most society directors, Olsen had his supporters and his detractors on the board and among the agency’s various constituencies. The board oversees operations of Historical Society, which runs the state historical museum, the state archives, a history magazine, the state historical preservation office and oversees certain historical buildings.

In a telephone interview Wednesday night, Olsen said his resignation was voluntary. He said he never intended to stay as director as long as he did. Olsen said he has never remained in any one job longer than eight years.

“I have a lot of diverse interests,” Olsen said. He said he wants to remain in Helena and would like to return to the Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks for the rest of his career before retiring in four or five years.

Asked if he received a financial settlement from the board to resign, Olsen said, “All of that is private.”

The press release announcing his resignation told how Olsen spearheaded efforts for the society before the 2005 Legislature’s to secure $7.5 million in state bonding for seed money for a new Montana History Center.

The society is considering the purchase of the land and buildings where the Capital Hill Mall is now located in Helena, a few blocks north of the Capitol and converting it to a new museum and headquarters, a project estimated to cost $40 million. The society is now completing architectural and engineering studies to determine if the mall is suitable for a history center.

Olsen said the timing of his retirement was in the best interest of the completion of the project.

“Looking at the timing of my retirement, I would not be able to see this important construction project through to completion and would not want to leave at a critical juncture,” he said in the press release.

He said he got the project to the point where it needed to be with the seed money from the Legislature and the support from Gov. Brian Schweitzer.

A number of private donors are stepping up now that they’ve seen the state’s commitment to the project, Olsen said.

“The future of the society is bright, and I feel good about the contributions I have been able to make toward its success,” Olsen said. “I wish the society and the board of trustees well as they move forward with their important work.”

Among his notable other accomplishments was the acquisition of the Robert M. Scriver collection to keep it in the state of Montana, the press release said.

Olsen was the ninth professional director to head the Historical Society since 1951, when historian K. Ross Toole headed the society for seven years. Before then, the society didn’t have professional administrators. The average tenure of its professional directors has been about five years.

The Montana Historical Society was created in 1865, a year after Montana became a territory, and became a state agency in 1891.

Friday, October 21, 2005

Sculpture Review, Fall, 2005

(Theme: Simplicity of Form)

There are only five articles in this magazine, which is about usual, but each of them is inspired and each of them relates to form in unexpected ways, so that the “synergy” is immense.

“Aztec Empire” presents alarming and yet somehow familiar monolithic figures, often with obsessively elaborate surface patterns -- almost brocaded. In addition are Halloween portraits of gobbling gods with their livers hanging out from under their ribs. One man, who appears to be covered with Post-It notes, turns out to have attached skin bits of a flayed slave, affixed to indicate the greening patches of spring. Skulls, teeth, and staring eyes are not what we would think of as “simple” maybe, but they certainly convey the simple fact of human flesh: vulnerable, horrible, suffering and ecstatic.

“Brancusi and Noguchi” balances abstraction against representation. Thumbed, blunt, minimal detail still somehow manages to contain personality and even recognizable persons. Brancusi takes minimalism so close to non-existence that tiny mineral flaws in the alabaster medium become significant and descriptive. They are like ghosts, souls, and yet -- because alabaster can be so like human flesh -- emotional. Noguchi makes two busts in bronze, nearly abstracted to featurelessness, but still somehow recognizable as George Gershwin and Buckminster Fuller (chrome plated).

“The Expression of Cleo Hartwig” shows portraits of women cut from stone, rather stylized, suggestive of some Native American work in the Southwest or, as she mentioned, Inuit (Eskimo) art.

“Luisa Granero” also does nudes, some of them in “caliza stone” which appears to be a kind of limestone and some in clay These are far more gestural and human looking women, round and strong in a classical way. Most are solitary figures, absorbed in their pursuits, but I especially liked the two small figures leaning together in “El Beso,” “The Kiss.”

“Simplicity of Form” by Nina Costanza, presents a series of figures -- all recognizable and all very different from each other. “Anemone” by Lorrie Goulet is coral-pink alabaster, curled on itself. “Maya” by Jose DeCreeft is black Belgian granite for a strong black face. “Small Goddess” by Betty Branch is a bronze just over a foot tall, a seated Venus with no arms or head, she is all butt and thighs in the manner of someone with a lot of estrogen and heft. The rest of the figures are all female, if you will accept a mother fox. The terrific turkey illustrating the table of contents didn’t make it into the story. I hope we meet it somewhere else.

In view of the great number of nudes, I was pleased to see an advertisement for anatomy figures, not just ecorche (skinned) but also with magnetic removable parts and deep muscle anatomy. Also, armature templates which I would think would be a wonderful advantage. Nothing is worse than laboring over a figure only to discover that a wire pokes through in the wrong place. $169 and up -- cheap at the price.

But if you haven’t got that much money on hand, the very next page over offers a $38 spiral-bound book of proportions: how long is a nose, what about an upper lip? Between which points ought one to measure anyway? These measurements are even more crucial for the faint hints on something like Brancusi heads.

I get as fascinated by the ads as I am by the stories -- which, of course, the advertisers hope will happen! The dino bronze across from the index just knocks me out! “Torosaurus Latis,” 21 feet long, 11 feet tall, mouth gaping, fabulous horns and shield ruff, beautiful blue-green patina -- oh, my! It you put it in your garden, you wouldn’t HAVE a garden because everyone would trample it in their efforts to touch this monster. Luckily, it’s going to the Peabody Museum at Yale. In its simplest form, of course, it was bones with the merest indications that it might look like this.

Giancarlo Biagi writes wonderful editorials, as one would expect from someone capable of editing in this tender but inexhaustible way. And I’ve begun to wonder how many years Ghandi has been walking quietly along on behalf of New Arts Foundry. He’s come to be a familiar friend.

My usual quibble is that I’ve had to take a hi-liter to the captions so that I can refer back and forth between figure and title without losing my place.

There are only five articles in this magazine, which is about usual, but each of them is inspired and each of them relates to form in unexpected ways, so that the “synergy” is immense.

“Aztec Empire” presents alarming and yet somehow familiar monolithic figures, often with obsessively elaborate surface patterns -- almost brocaded. In addition are Halloween portraits of gobbling gods with their livers hanging out from under their ribs. One man, who appears to be covered with Post-It notes, turns out to have attached skin bits of a flayed slave, affixed to indicate the greening patches of spring. Skulls, teeth, and staring eyes are not what we would think of as “simple” maybe, but they certainly convey the simple fact of human flesh: vulnerable, horrible, suffering and ecstatic.

“Brancusi and Noguchi” balances abstraction against representation. Thumbed, blunt, minimal detail still somehow manages to contain personality and even recognizable persons. Brancusi takes minimalism so close to non-existence that tiny mineral flaws in the alabaster medium become significant and descriptive. They are like ghosts, souls, and yet -- because alabaster can be so like human flesh -- emotional. Noguchi makes two busts in bronze, nearly abstracted to featurelessness, but still somehow recognizable as George Gershwin and Buckminster Fuller (chrome plated).

“The Expression of Cleo Hartwig” shows portraits of women cut from stone, rather stylized, suggestive of some Native American work in the Southwest or, as she mentioned, Inuit (Eskimo) art.

“Luisa Granero” also does nudes, some of them in “caliza stone” which appears to be a kind of limestone and some in clay These are far more gestural and human looking women, round and strong in a classical way. Most are solitary figures, absorbed in their pursuits, but I especially liked the two small figures leaning together in “El Beso,” “The Kiss.”

“Simplicity of Form” by Nina Costanza, presents a series of figures -- all recognizable and all very different from each other. “Anemone” by Lorrie Goulet is coral-pink alabaster, curled on itself. “Maya” by Jose DeCreeft is black Belgian granite for a strong black face. “Small Goddess” by Betty Branch is a bronze just over a foot tall, a seated Venus with no arms or head, she is all butt and thighs in the manner of someone with a lot of estrogen and heft. The rest of the figures are all female, if you will accept a mother fox. The terrific turkey illustrating the table of contents didn’t make it into the story. I hope we meet it somewhere else.

In view of the great number of nudes, I was pleased to see an advertisement for anatomy figures, not just ecorche (skinned) but also with magnetic removable parts and deep muscle anatomy. Also, armature templates which I would think would be a wonderful advantage. Nothing is worse than laboring over a figure only to discover that a wire pokes through in the wrong place. $169 and up -- cheap at the price.

But if you haven’t got that much money on hand, the very next page over offers a $38 spiral-bound book of proportions: how long is a nose, what about an upper lip? Between which points ought one to measure anyway? These measurements are even more crucial for the faint hints on something like Brancusi heads.

I get as fascinated by the ads as I am by the stories -- which, of course, the advertisers hope will happen! The dino bronze across from the index just knocks me out! “Torosaurus Latis,” 21 feet long, 11 feet tall, mouth gaping, fabulous horns and shield ruff, beautiful blue-green patina -- oh, my! It you put it in your garden, you wouldn’t HAVE a garden because everyone would trample it in their efforts to touch this monster. Luckily, it’s going to the Peabody Museum at Yale. In its simplest form, of course, it was bones with the merest indications that it might look like this.

Giancarlo Biagi writes wonderful editorials, as one would expect from someone capable of editing in this tender but inexhaustible way. And I’ve begun to wonder how many years Ghandi has been walking quietly along on behalf of New Arts Foundry. He’s come to be a familiar friend.

My usual quibble is that I’ve had to take a hi-liter to the captions so that I can refer back and forth between figure and title without losing my place.

Friday, October 07, 2005

A Video Portrait of Charlie Russell

“A Portrait of Charles M. Russell, Preserver of the Old West” is a VHS video that lasts about an hour. You can buy it at the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls, but the maker is “High Hopes Productions,” PO Box 20369, Seattle, WA 98102, (206) 322-9010. I bought it because it has Bob Scriver in it, but it’s really about Charlie.