“March in Montana”, one of the Great Falls auctions that hitchhikes on the major auction in celebration of Charlie Russell’s birthday, is “featuring” sculptures by Bob Scriver and Earle Heikka. There are points of similarity between the two men and also significant points of difference. Heikka and Scriver both had backgrounds in taxidermy at museum levels where dioramas are the goal. Both are local, Heikka born in Belt and Scriver born in Browning. Heikka (1910 - 1941) was older than Scriver and committed suicide while Scriver was in the service in Edmonton, before the latter began serious sculpture. They were not acquainted. Both men did Western genre subjects: pack trains, cowboys and Indians, and stagecoaches, but Scriver’s work included many other subjects including portraits and a small group of religious works. He's best compared to the French school of Beaux Arts sculptors who created many of our familiar monuments: men like Fraser, Procter, Saint Gaudens, and so on.

Heikka worked in a very difficult medium, “Marblex,”something like paper mache which cracked badly when it dried. It required much patience to master and didn’t receive or hold detail very well. As far as I know, Heikka didn’t cast them in bronze during his lifetime. His pieces were one-of-a-kind, hand-painted.

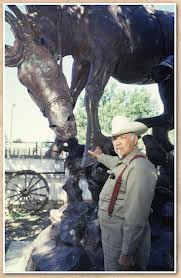

In contrast, Scriver worked in plastilene, was a master mold maker, and built his own foundry, the Bighorn Foundry, in order to have total control. The bronzes cast in those days were silicon bronze using the Roman block method and had a very specific patina meant to be like those of the Animaliers cast in Paris in the 19th century. They were numbered in small editions, certificates were issued, and sales were recorded in a master book that appears to have gone missing since the Montana Historical Society, who received Scriver’s estate, can’t seem to locate it. Possibly it was intercepted before the estate was moved.

In the early days Scriver cast in hydrocal, a very hard version of plaster, and he kept a key casting of each piece in case something happened to the mold. (Since metal shrinks when it is cast, molds made from previous bronzes will be slightly smaller.) It appears that one of the pieces in this auction is one of those key castings. If the mold was made from black tufy cold molding compound, it would leave the piece discolored like this. It's hard to know how to value something like this. We used to set the price of hydrocals as one-tenth the price of the bronze, but if it were the mold key, it would be worth far more as a production basic. It's not much to display and could easily be broken if struck or dropped. It ought to have been destroyed at Bob's death.

Lone Cowboy, 1880. Created in 1968, no edition numbers. This specific piece was a companion to the original “Lone Cowboy” which was Bob’s trademark for many years. It was also a “breakthrough” in a different way, the first of Bob’s work that was consciously designed. It was the piece Warren Baumgartner, a master watercolorist from NYC, helped with in order to teach Bob composition. Heikka never had the benefit of such lessons.

One of the most complex of these composed sculptures is “Real Meat”. Created in 1964 , numbered 8. Original certificate included. The phrase is the original Blackfeet name for buffalo. These animals are specific buffalo that Bob measured and studied at the Moiese National Bison Range. The men were modeled by members of the Kicking Woman family and the horses are taken from Bob’s own horses. This large piece is in a different scale, a different style, and a different composition from the Russell sculpture to which is it sometimes compared.

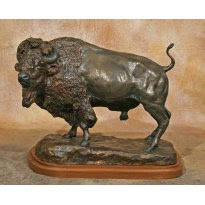

"The Hornaday group" is a famous remnant taxidermy group in the Smithsonian. Since it was showing signs of age and needed some refurbishment, this bronze was created for sale to finance that work. Inscribed "Special to Loran & Delores Perry" which means it was not numbered.

Other buffalo portraits include “Herd Bull” which is the study for the buffalo bull that once stood in the Scriver Museum of Montana Wildlife. This is #5 of 110. It claims to be cast by the Proctor family in the '70's. I know nothing about that. 110 is a large edition.

The “breakthrough into bigtime" notice came with the large rodeo series that developed out of the commission from the Professional Rodeo Cowboy Association to do an heroic-sized portrait of Bill Linderman. The Calgary Stampede bought a complete set of these bronzes. These pieces have only recently begun to show up in auctions.

The most spectacular and graceful is “Paywindow,” the bucking horse on one foot. It is nearly balletic. This is numbered 17 and was cast in the Bighorn Foundry, Bob's own. Original certificate is with it.

"Not for Glory" is the pickup men, one taking off the rider and the other getting hold of the horse. This is copy #2, cast in the Bighorn Foundry, Bob's own. Original certificate included.

"Headin' for a Wreck" is the steer-wrestling event. Those in the know would see that the cowboy's timing is just enough off to make trouble. This is the #6 casting and was cast by Powell Bronze Foundry, which was run by Eddie Powell, Ace's oldest son.

Later there were smaller “cowboy” pieces. This one is old-timey and uses Bob’s longhorn steer, “Tex.” He called it "When Cutting Was Tough." #55 of 110. Arrowhead Bronze Foundry. This foundry used ceramic shell casting. The high numbers were common with Bob in the later years. There is no "law" -- not even business law -- that controls the number of castings in an edition. Severely limiting the number was a convention in the early days when molds lost detail in every casting. It was a gentleman's agreement that Bob came to despise as bad business practice since modern molds don't lose detail.

Bob liked to work in groups around a subject. The Lewis & Clark monument commissions for Great Falls and Fort Benton were financed by the sale of smaller castings, sometimes replicas and sometimes on the same theme.

"Captain Lewis & Our Dog Scannon" turned out to be misnamed. The dog's actual name was "Seaman." Arrowhead casting. The dog that posed for this Newfoundland dog was named "Windsor." This is casting # 26 of 150. The dog (and the slave York) actually belonged to Clark.

"Capt. Wm. Clark, Map Maker." #26 of 150. Arrowhead casting. Actually, he's surveying here and will record numbers from which maps can be constructed. Since this casting has the same number as the one just previous, they were probably sold together.

"Lewis, Clark & Sacajawea", #25 of 35, is a small version of the Fort Benton monument. Actually Pompey is in it as well. Created in 1974. The Certificate of Authenticity that comes with it is issued by the Lewis & Clark Memorial Committee.

This “set” is a series of “collectibles” on the theme of coffee, suggested by an entrepreneur.

Coffee Break Series: "Coffee Break," "Batwing Chaps," "Wells Fargo Cargo," "Bull Durham Cowboy" and "The Sheriff." Set #141/250. Arrowhead castings.

Coffee Break Series: "Coffee Break," "Batwing Chaps," "Wells Fargo Cargo," "Bull Durham Cowboy" and "The Sheriff." Set #141/250. Arrowhead castings.

A few other individual old-timey pieces might be commissioned or just be inspired by reading or conversation.

"Defending the Mail" created in 1989. #27/150. Arrowhead casting.

"Salute to the Buffalo Robe" is inscribed "Special to Loran & Delores Perry" so is not numbered. Created in 1995. Commissioned to celebrate the 150 anniversary of the establishment of Fort Benton and includes a certificate of authenticity from the Fort Benton Committee as well as being inset with a Fort Benton 150th anniversary medallion.

"Defending the Mail" created in 1989. #27/150. Arrowhead casting.

"1861 Mail (Pony Express)" Created in 1991. #7 of 100.

"Montana Trapper." #96/100 Created 1976. Arrowhead casting.

Of course, Scriver continued with the animal pieces. This one revisits the idea of two bull elks fighting over a cow, but uses a different composition.

"To the Victor" #54/75 Arrowhead casting. Late in life Scriver's human figures seemed distorted sometimes, but his animals always kept their anatomical accuracy. One could look at the high number sold of this piece as either damaging its value because it's not very scarce, or could see it as an indicator of popularity, which is always good for sales.